Our daughter passed away as a result of startling hospital errors, and we feel like such fools.

Martha, 13, was busy last summer. She’d meet friends in the park, make goofy films, and play “kiss, marry, kill.” Books and music lyrics filled her days. She pondered becoming a novelist, engineer, or film director. Her future held promise and dreams.

By summer’s end, she was dead after appalling errors at a top UK hospital.

What follows is a description of how Martha died, but also what happens when you put naive faith in doctors and learn too late how to save your child’s life. I’m sharing what I’ve learnt. Martha’s story may change some people’s views on healthcare and save a life.

I support the NHS and know many brilliant doctors work there. Martha’s death had nothing to do with austerity, cuts, or a strained health service, as confirmed by the hospital.

No matter how often I’m told “it was the physicians’ job to care for Martha,” I know deep down that if I’d acted differently, she’d still be alive and my life wouldn’t be broken.

The hospital admitted breach of duty of care and a “catastrophic error.” I’m not to blame. My kid would be with me if I’d known how hospitals and physicians function.

Life after your child’s death is like being on an island, away from “normal” people. You long to return but can’t. Forever on the island.

I rented a cottage near Snowdonia. It was a modest, ancient farmhouse with low-hanging beams and no wifi or phone connection; parking was at the bottom of a sheep-grazing slope.

Martha and Lottie requested rides in the wheelbarrow with our stuff. First day, we bodyboarded on Barmouth beach and painted the cottage’s valley vista. We ate in a tavern and played cards; everything was light and pleasant.

The second day, we hired bikes and rode nine miles of old railway to the shore and back. The path is attractive, flat, and family-friendly, according to a guide. I recall riding with Martha and discussing body hair (she wanted to know if she should shave her armpits).

We ate crab sandwiches and fries while swimming. Soon after we returned to our bikes, Martha stumbled on a beach-blown sand patch. She was pedaling carefully — we called her “Captain Sensible” — then she crashed and started making zombie sounds.

She crawled near the edge to avoid other bikes. Another family with a younger child cycled by while we waited. This girl likewise skidded but stayed upright, so the family continued. They won’t forget that moment.

We transported Martha to a minor injuries unit because she wasn’t better. We spotted a red ring on her tummy when she lifted her T-shirt for examination; she had landed on one end of her twisted handlebars. Only an O-shaped mark was seen.

The nurse explained Martha’s injury to a doctor, who claimed he didn’t need to visit her and gave paracetamol. I debated whether to urge the doctor look at her, but I didn’t and we went home. 2am, Martha was unwell and in pain, so we took her to A&E.

“I can’t make it down the slope to the car,” she said, so her dad carried her in a wheelbarrow while Lottie held a phone as a torch. Martha was carefully loaded into the automobile.

In Aberystwyth, they ran tests and kept her overnight for observation. At daybreak, a doctor with a solemn expression told us Martha probably suffered pancreatic trauma: her pancreas had been pressed against her spine, causing a laceration.

I knew the injury was bad but trusted the system. Two years of Covid had us constantly praising the NHS to the girls. Martha and Lottie painted thank-you rainbows for our window. We stood outside the door on Thursdays and clapped; Martha pounded a skillet with a spoon.

I was so certain in her recovery that I started gathering images as props for her summer misadventure story. First, she’s asleep in her Aberystwyth hospital room. Next, she’s outside the chopper that carried us over the Brecon Beacons to Cardiff. Both she and the paramedic wave to the camera.

Martha was rushed to Cardiff’s intensive care unit and hooked up to bleeping monitors. She received one-to-one care; a nurse stood behind a lectern at her bed. We’d never been hospitalized before, so I was concerned, but a doctor reassured me, “It’ll be a tough few days, but she’ll be alright.”

Googled already. Pancreatic trauma in adults is commonly found with other organ damage in car crash or shooting victims. I thought of the “O” on her stomach as a bullet wound without the bullet.

In children, BMX jumps and tricks gone wrong are common causes. Identifying the injury promptly is important before acidic pancreatic secretions cause too much harm. I was delighted we made the midnight hospital run.

Martha was flown from Cardiff to King’s College Hospital in London, one of three pancreatic injury centers in England. She was placed on Rays of Sunshine ward, which is well-funded through NHS money, donations, and private patients’ payments.

Martha had a glass cubicle with a TV; the ward had modern equipment and a playroom. We were assured, “You’re at the best position.” In thanks, I signed up for the Great Hospital Hike, a September fundraiser for King’s. Paul and I said, “We’re so lucky”

Martha was unlucky. Her injury was curable, but she died after irresponsible treatment at King’s. A hospital official called her preventable death a “bad consequence” Why did my child have such an unusual fate?

I became pregnant with Martha at 29 and it happened so fast I wasn’t sure. I enjoyed my career, life, and independence. I feared being a parent would limit my style because I was too selfish. When she emerged damaged from being within me the wrong way, I was altered. I told a friend I felt punched by love.

People told us we were amazing parents because she was so easy. We appreciated the praise, but she was just happy and calm. She used to say, “I’m as jolly as a jolly-bird,” to describe her personality.

Paul and I took turns sleeping next to Martha on Rays of Sunshine. We were assured daily that her recovery was a matter of time and patience. After two weeks, friends visited her in the hallway.

One doctor said, “I’m going on vacation and hope not to see you.” We became used to the ward routine: nurses taking observations, early morning blood tests, the youngster next door with pancreatic trauma from a handlebar accident. We hung cat photos in our cubicle.

I got food in the hospital lobby. On my way down, I observed two angry women. One woman screamed, “Fackin’ murderers!” She was loud. “Let’s escape the murderers!” shouted the other as they left. I automatically sided with the physicians.

Martha was tube-fed milky formula. She stared wistfully at lasagne and roast potatoes on her phone during hospital days. In between milk feeds, I’d give her a bath with homemade bath salts.

She’d relax in the tub with her blond-tipped brown hair fanning out behind her in the water. I washed her clothes when she was young.

We saw a different consultant every day and wondered who was in charge of Martha’s care; I wish we’d done more. During ward rounds, we asked consultants how the treatment worked. We attempted to be expressive and grateful; we wanted to bring out the best in the professionals. Medical notes judged us. “Parents friendly and helpful,” reads one entry.

Junior doctors deferred to the consultants ostentatiously. They were talkative and grand. We heard about a study paper “Prof Bow Tie” was supposed to give in Athens; he uploaded the view from his luxurious hotel on Instagram after Martha died.

After ward rounds, junior doctors cared for Martha. I assumed they knew everything about Martha’s care because they were young and confident. Naive me didn’t realize they were training.

Martha used a changeable toy octopus with a happy or sad face to mark her good and bad days. After a few weeks in the ward, she got a fever on 21-22 August. Martha feared the frowning octopus.

I applauded her boldness and promised there was another side. I told her, “This hospital is great.” She shivered, had diarrhoea, and retched into cardboard bowls we held under her face.

Doctors predicted medications will cure the condition in 72 hours. “What if they fail?” “Martha?” It was promised. “But if not?” “Yes,” For her fever and back ache, we gave her ice packs and hot water bottles.

She’d wander into the hallway and stand beneath the air conditioning vent, bending her head back to feel the cold. I’d put my arm around her shoulders to help her to bed.

During her therapy, we expected short-lived infections. Martha’s fever remained Wednesday. Worse, she started bleeding from her arm line and abdominal tube. Blood seeped through her bandages, pajamas, and bedding. After she died, we learned that her unusual bleeding was a sign of acute sepsis.

While the physicians knew she had sepsis, they just said “infection” to Paul and me. If they had, I’d have known more. Martha’s “clotting abilities were slightly impaired,” a “common virus side-effect.”

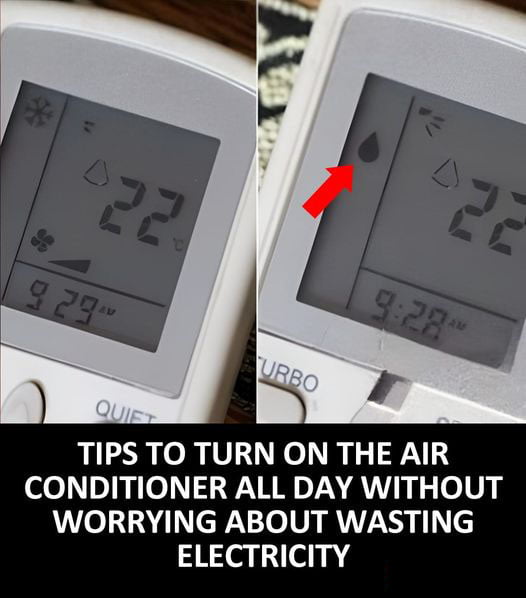

Hospitals employ a system called BPEWS (Bedside Paediatric Early Warning Score) to help doctors and nurses decide whether to report concerns about child patients. On Wednesday, Martha’s BPEWS was six, a high score, and she should have been transferred to intensive care.

Living with a child changes you: It’s still hard to stop her nice habit a year after her death.

Martha kept bleeding on the ward. The medical papers show I was “extremely distressed,” but the doctors assured me she’d “turn a corner.” A scan revealed fluid around her heart, another indicator of sepsis. We weren’t alerted about the postponement until after the holiday weekend.

Severe sepsis can be managed with potent medications and repeated interventions in intensive care. Martha might have gone to the PICU down the hall, which had free beds. Her consultants avoided PICU.

A year after Martha’s death, it’s hard to break the pleasant habit of her. I remember her unraveling undergarments and throwing them at our heads. Her laugh was a gift: nothing matched her head-thrown-back, stomach-grabbing laughs.

She liked making fun of her dad for cycling into the canal. She liked hearing about Paul and my engagement. Her cello, melodies, and poems. She mapped out a novel at the start of the summer, and her notebooks were full with story ideas (“The Story of Nothing”: “Every book starts with nothing. Nothing is male. This is how Nothing becomes Something.

At Martha’s memorial, a school classmate observed, “For me, there were two sides to Martha: the one who danced with me on the train platform; the one who strapped a PE bag on her back and called herself a turtle.” Then there was the woman who quietly sung as I rode home. She was always there for me, and I was too.

Martha’s bleeding stopped Friday morning after physicians gave her clotting agents. By lunchtime, she was crying over her fever. She didn’t want to read or play Minecraft on her phone with friends. She ignored my suggestion to watch Lin-Manuel Miranda’s latest film.

The bank holiday weekend was approaching, and the physicians didn’t know the cause of the infection. On weekends, the ward was strangely silent as the on-call consultants went home. Long weekend and fever were worrisome.

We identified the connection between infection and septic shock, a common cause of hospital fatalities. I told that day’s consultant, “I’m scared Martha will go into septic shock on a holiday weekend when none of you will be present.” The consultant scanned numbers. She doesn’t fear sepsis. Martha’s brows furrowed when I returned to my cubicle. “Septic shock was mentioned,” I told her, “Don’t worry.” “I must make sure they consider everything.” “It’s simply an infection,” the consultant said as she left.

The leader of the team of consultants reassured Paul on Saturday morning, “Infections come and go with this ailment.” Martha’s fever persisted, and when she tried to rise, she felt dizzy. Paul said, “This is new.”

I was with Martha on the holiday Sunday. During that day’s ward round, “Prof Checked Shirt” whispered to a surgeon outside Martha’s cubicle. She was considerably worse than expected. They didn’t tell me, and I didn’t see them again that day. Martha was left with two junior doctors, one, “Dr Blunder,” more experienced than the other.

Oxford-educated Prof Checked Shirt, in his late 50s, went for home early in the afternoon. In his absence, he played a key role in Martha’s death. She had sepsis, a high fever, low blood pressure, and a pounding heart by noon. The writer of King’s Serious Incident report on Martha’s death told me she should have been moved to PICU.

Nurse: “Trust the doctors.” It’s the worst advise I’ll ever get.

The day’s professor, Checked Shirt, never considered it. High-status consultants on Rays of Sunshine (“level sevens” in seniority) were disdainful of less senior colleagues in PICU (“level fives”). Inflated egos made them unwilling to provide intensive care for Martha.

Sunday afternoon, she had a red rash on her legs, neck, and body. Rash indicates sepsis. Dr. Blunder, despite Martha’s other symptoms and lack of experience, was confident the rash was a delayed medication reaction. I told him it was a sepsis rash, but it didn’t help.

I left Martha’s cubicle to find an ally and grabbed a nurse. “I fear he’s wrong. I’ve searched online.” Nurse stopped and touched my arm. “Don’t google stuff,” she advised, “you’ll worry.” “Trust the physicians, they know what to do.” I listened. The worst I’ll ever get.

I admired Martha’s quiet confidence. By the time daughter reached high school, she hadn’t worn a skirt in a few years, and I knew that while girls may wear pants, most wore skirts. How would she cope? Should I get her a backup skirt? “Just pants,” she said. Before the first semester, she compared notes with classmates. “Skirts, right?” “Definitely skirts.” I watched Martha as everyone agreed. She whispered, “I like pants.” She donned pants, and others followed.

Martha never kissed. Her classmate laughed at her favorite phrase, “defenestration.” We never saw how her other crush fared. We discussed gender and sexuality in the hospital. Do you ever wonder if you’re gay? “I’m heterosexual,” she said. Maybe I haven’t met the proper woman yet.”

The coroner at Martha’s inquest called Dr. Blunder’s misdiagnosis “such a blunder.” Even unpressured professionals make mistakes, but rarely so egregious. What occurred next baffles me.

5pm, Martha’s BPEWS score was 8. Dr. Blunder called home to notify Prof. Checked Shirt. The consultant declined. Though he wasn’t convinced of Dr. Blunder’s diagnosis, he didn’t suspect sepsis. Dr. Blunder spoke to him again, but no adjustment was needed in Martha’s care. Due to hospital structure, no one took the initiative. She remained calm.

Prof Checked Shirt painted a partial picture of Martha’s condition when he called from home that evening. He didn’t mention her bleeding or new rash. Intensive care “categorically” shouldn’t visit Martha’s bedside, he said: “no review was needed” and it would raise my concern. He decided to go against hospital policy and calm frightened parents.

The PICU chief said there was a bed if needed. If Prof Checked Shirt had given him the complete picture, would Martha have been sent to intensive care? He said, “100%.”

After Martha’s death, Prof. Checked Shirt was reluctant to call his actions a “mistake,” even though colleagues had identified it. At least five times, Martha’s care should have involved PICU, according to the hospital study. No doctor warned me she was in danger. I was misinformed and patronized. Misogyny permeates my legitimate concern.

Paul and I didn’t know critical care was the best place for Martha. We didn’t know enough to challenge or insist she be moved. So we failed to defend our child while she was in danger. Always guilty

Dr. Blunder’s evening shift welcomed a new junior doctor. Martha needed “continuous monitoring” (After Martha died, King’s computer lost the handover notes.) Who knows why a blood test wasn’t done; it could have saved Martha’s life. A request for one-on-one care was ignored.

This young doctor (“Dr Do-Nothing”) never visited Martha, the ward’s sickest patient, despite the nurse’s concerns.

I told Martha she’d survive. She remarked, “You’ve said that so much it’s meaningless.” She felt parched all night. She gasped, “Water” repeatedly. She couldn’t get enough despite my refills.

I told the nurse, “She’s drinking insane quantities of water.” I was exhausted and didn’t realize this was a warning. Dr. Do-Nothing still didn’t want to see my daughter.

Martha needed the bathroom around 5:45am. As she sat down, her body tightened and her eyes rolled. As she convulsed, I grasped her. Her body trembled in my arms as diarrhoea gushed from her. Not enough blood got to her brain, causing a seizure due to sepsis.

I panicked and said, “What’s wrong with her?” The nurses fussed over her after she woke up. In sobs, I gathered the senior nurse, who told me my kid wouldn’t die and to calm down.

Face cleansed, I returned to my cube. Martha and I were alone when she looked at me with concern and stated, “It feels unfixable.” These words frighten and worry me at night.

Dr. Do-Nothing only realized her patient was sick after the blood test. Martha was rushed to intensive care too late to stop septic shock. That evening, Martha was transferred to Great Ormond Street children’s hospital to be hooked to a heart-lung machine. Ineffective. Tuesday morning, Martha died.

The last day’s tragedies might fill pages. Let me describe her clear move out of Rays of Sunshine. PICU clinicians flooded Martha’s cubicle. I begged, “Please make her better by Saturday.” Birthday.

Martha thought an oxygen mask in intensive care was an anesthetic to put her to sleep. She pointed to the mask and remarked, “This isn’t working.” I told her it was oxygen, but she didn’t hear.

In seconds, they shoved a tube down her throat; she gagged and arched her back before the tranquilizer took effect. I repeatedly said, “I love you.” Martha fell into a permanent coma.

I know many facts of Martha’s deterioration from the report, questions we’ve asked King’s since her death, and the inquest, which found that her doctors failed to heed the warning indications and move her to PICU.

Hospitals must be honest about errors. King’s behaved better than some, but there were restrictions and unsolved problems.

The hospital trust apologized but remained vigilant. Improvements were discovered, which is why everyone at King’s was more comfortable discussing “systems” than physicians’ acts.

The trust closed ranks and we entered the tired realm of institutional condolences and “lessons learnt.” A hospital will safeguard its doctors from their tragedies.

Martha’s was one of 150 needless deaths in the NHS per week.

How could they have known? My life has ended. After Martha’s death, Dr. Blunder was elevated to consultant. I’m sick, miserable, and confused every day. My father died when I was 10, but I’ve only recently comprehended grief. Many people walk in shadow, “regular” existence a distant memory. I’d be dishonest if I didn’t acknowledge that deaths and grieving are different.

Martha’s death was preventable (one of 150 in the NHS every week). Most people prefer to deal with a heroic “fight” with illness than a death caused by medical mistakes, especially that of a child — the most unfaceable fear. After Martha died, we got a card that said, “You’ve experienced what we all fear.”

As stupid or insensitive as it seems, I envy other children’s deaths. One parent whose daughter died of bone cancer took comfort in discovering that Spain’s football manager lost his kid to the same sickness. “If he couldn’t accomplish anything with all his money and celebrity, nothing could be done,” the father said. I’m not comforted.

This isn’t the place to argue for a “no-blame” or “just culture” NHS. Our trust in doctors should be limited, which is apparent yet rarely addressed. Medicine is like any other job: the NHS has both skilled and less-dedicated professionals.

What do you call the last-place medical student? “Doctor.” Arrogant and complacent clinicians abound. We shouldn’t consider all doctors “heroes.”

Don’t be scared to criticize NHS decisions if you have good reason. Keep your cool. Most hospital doctors are trainees. Ask a clinician about their experience.

Junior doctors are generally inexperienced and striving to impress. If possible, give one consultant entire responsibility; when you’re accountable, you work harder.

Ignore advice and search online. Google, educate yourself, ask questions, and if doubtful, get a second or third opinion. You may be “managed” and “reassured” but not told the truth. Nope.

Weekend hospital care is less thorough. Understand the harm caused by the aristocratic, hierarchical structure, where everyone defers to the senior consultant. Shout the ward down if things go wrong. Not doing so would have cost too much. We trusted so much; we’re fools.

I’m now an islander. We visit Martha’s grave instead of hosting her. Some headstone inscriptions would have delighted her: “Philosopher, Teacher, Nudist,” “International Man of Mystery,” “Forever Loved, Always Right.”

But her gravemates survived seven or eight decades. Martha should have left hospital like other injured youngsters. Now Lottie has an empty bedroom and a park bench with a plaque: “To my sister.”

I wish Martha had received timely critical care and been saved. My daughter reaches 14 in this parallel dimension. I constantly praise her physicians and nurses. I walk for charity. Martha aced all her examinations and went to a good university.

I can picture her drinking, enjoying college life, and smiling. Soon after starting secondary school, she noted in her diary, “GCSEs could affect my whole life.” In my fantasy, Martha has a career and children. We remember her hospitalization when she visits on weekends.

I’d love to live there.